Table of Contents

BCCI: Cricket’s Beginnings in India: From Kutch to Calcutta

BCCI The year 1721 holds little political significance for India, as the Mughal Empire was in decline after Aurangzeb died in 1707. While the Marathas were asserting dominance and challenging Delhi, European merchants from England and France had quietly established trading settlements along India’s coasts. One such settlement witnessed the earliest reference to cricket in India.

In 1721, a British ship anchored off the Kutch coast in western India. The sailors’ recreational activities, including cricket, drew the curiosity of locals. One sailor, Downing, documented these moments in his memoirs, noting, “We ever diverted ourselves with playing cricket and other exercises.” This marks the first recorded instance of cricket on Indian soil. By 1751, the British army and English settlers held the first recorded cricket match in India.

The sport began formalizing in 1792 with the establishment of the Calcutta Cricket Club (CCC), the second-oldest cricket club after the MCC. By 1802, the club hosted a significant match where Robert Vansittart scored the first recorded century in India.

BCCI The Rise of Indian Cricket: From Sepoys to Gymkhanas

Cricket’s popularity quickly spread among the locals. Indian army ‘sepoys’ were some of the earliest adopters, engaging in matches against their European officers. The Parsis became the first Indian civilian community to embrace the sport, forming the Oriental Cricket Club in 1848, followed by the Young Zoroastrians Club in 1850. Other communities, such as Hindus and Muslims, soon followed, with prominent institutions like the Hindu Gymkhana in 1866 and the Parsi Gymkhana in 1884.

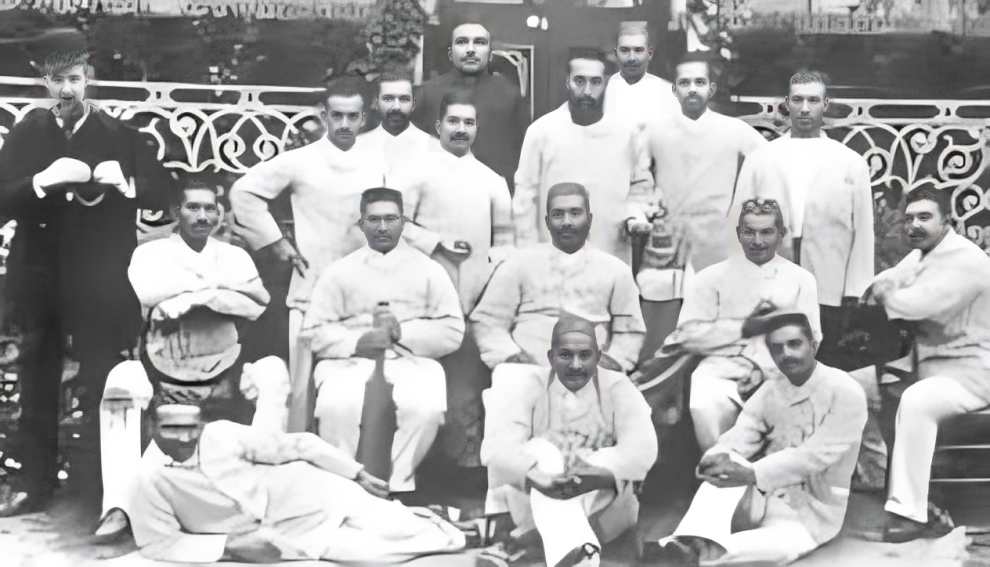

The Parsis also made significant strides internationally, sending their first team to England in 1886. Though they struggled initially, the second tour in 1888 was more successful, highlighted by Dr Mehellasha Pavri’s 170 wickets. By 1890, cricket had permeated India’s princely states. Kumar Shri Ranjitsinhji’s remarkable success in England inspired Indian royalty to further support the sport.

These developments led to the introduction of communal tournaments like the Quadrangular and later the Pentangular. The 1911 All-India team’s England tour, led by the Maharaja of Patiala, was another milestone, showcasing talents like Baloo Palwankar, an inspirational figure who overcame social barriers.

By the 1920s, Indian cricket was ready for the international stage. C.K. Nayudu’s spectacular innings against the MCC in 1926 further convinced British authorities of India’s potential. The groundwork for India’s entry into Test cricket was laid, marking the beginning of a historic journey.

Govan, Patiala and De Mello in turn assured Gilligan that they would do their bit. They convened a meeting in Delhi on 21st November 1927, which was attended by around forty-five delegates. These comprised cricket representatives from Sind, Punjab, Patiala, Delhi, the United Provinces, Rajputana, Alwar, Bhopal, Gwalior, Baroda, Kathiawar and Central India. There was a consensus that a Board of Cricket Control was essential to ensure the following:

Advance and control the game of cricket throughout India.

Arrange and control inter-territorial, foreign and other cricket matches.

Make arrangements incidental to visits of teams to India, and to manage and control All-India representatives playing within and outside India.

If necessary, to control and arrange all or any inter-territorial disputes.

To settle disputes or differences between Associations affiliated with the Board and appeals referred to it by any such Associations.

To adopt if desirable, all rules or amendments passed by the Marylebone Cricket Club.

Another meeting, held at the Bombay Gymkhana on 10th December 1927, ended with a unanimous decision to form a ‘Provisional’ Board of Control to represent cricket in India. The plan was for this ‘Provisional’ Board to cease to function as soon as eight territorial cricket associations were created. Representatives of the eight associations would then come together to constitute the Board.

Govan and De Mello visited England in 1928, where they made a case on India’s behalf in front of the ICC. Their deliberations were satisfactory, but it turned out that their efforts had not been complemented in their absence. In late 1928, only six associations – Southern Punjab Cricket Association, Cricket Association of Bengal, Assam Cricket Association, Madras Cricket Association and Northern India Cricket Association – had been formed.

The Provisional Board met in Mumbai in December 1928 during the Quadrangular tournament, to discuss the next course of action. It was at this meeting that Govan and De Mello prevailed upon the others to reconsider the decision taken at the previous year’s meeting. They did not want India to miss out on the opportunity to host South Africa in 1929 and tour England in 1931!

Their persistence paid off. The Provisional Board was deemed to have finished its work, and the Board of Control for Cricket in India was established. Govan was the first President, and De Mello the first Secretary. Five months later, the ICC admitted India as a Full Member.

Some favoured Delhi and Calcutta as likely bases of the board, but it was Bombay that finally won. The city’s cricketing ethos and cosmopolitan nature were believed to have given it the edge

Political developments on the subcontinent put paid to the prospects of the series against South Africa and England. India had to wait till 1932 to become a Test-playing nation.

Govan and De Mello tried their best to convince Kumar Shri Duleepsinhji, nephew of ‘Ranji,’ to lead the Indian team to England in 1932. Not only was ‘Duleep’ a prince, but he was also a successful cricketer in his own right, having scored a century on his Test debut for England against Australia in 1930. But Duleep declined. It was later alleged that he had been asked to refuse by none other than his uncle, who had given the impression of not being too interested in Indian cricket.

In the prevailing circumstances, the Maharaja of Patiala fancied his chances of becoming the leading figure in Indian cricket. But he had to contend with Lord Willingdon, the then Viceroy, who did not get along with him, and the Maharajkumar of Vizianagaram, who pulled off a coup in 1930-31 by inviting Jack Hobbs and Herbert Sutcliffe, two of England’s best batsmen of the time, to play in India.

Patiala was initially flustered by Willingdon and Vizianagaram, but he regained his composure at the annual meeting of the BCCI in November 1931. He offered to host and finance the selection trials of the team that was to undertake the historic tour in 1932.

Prince Ghanshyamsinhji of Limbdi was appointed vice-captain of the squad that Patiala himself was designated to lead. However, Patiala withdrew, and the reins were entrusted to the Maharaja of Porbandar.

On the eve of the inaugural Test, which was played at Lord’s in 1932, both Porbandar and Limbdi pulled out, and Col. C.K. Nayudu, the premier cricketer in the squad, was awarded the honour of becoming India’s first Test captain.

‘Team India’ underwent a ‘baptism by fire’ from 1932 to 1952 before opening its account in Test cricket. The fifth and final Test of the 1951-52 series against England at Chennai was won by an innings and eight runs. A year later, the Indian cricketers registered their first-ever series win against compatriots-turned-foreigners Pakistan.

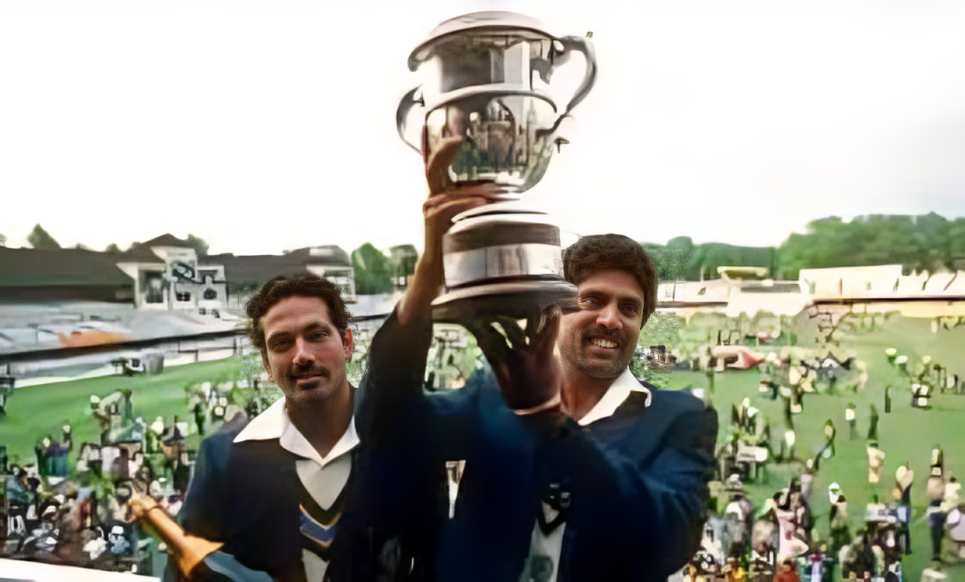

India first won a Test series abroad in 1967-68, when the New Zealanders were beaten 3-1 on their pitches. Three seasons later, the Indian team went several steps further, winning back-to-back series in the West Indies and England.

The country’s unexpected triumph in the World Cup in 1983 emboldened the BCCI to bid for the 1987 World Cup along with its Pakistani counterpart. It was the first time anyone had even thought of staging the competition outside England. The bid was upheld by the ICC, and the neighbours went on to stage a hugely successful event, the doubts raised by cynics notwithstanding.